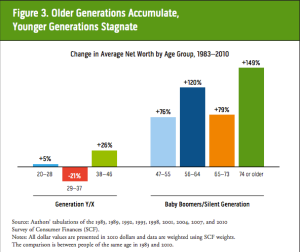

“Today’s adults in their mid-30s or younger—the prime time for career and family formation—benefited little from the doubling of the economy since the early 1980s and have accumulated no more wealth than their counterparts 25 years ago.”

The Great Recession hasn’t really been kind to any particular age cohort, but it’s highlighted how severely Generation X and Y have been left in the dust by the Baby Boomers. The Urban Institute recently released some research detailing the specifics:

Despite the recent recession, our economy in 2010 was about twice as rich both in terms of average incomes and net worth as it was 27 years earlier in 1983. But not everyone shared equally in that growth.

Younger generations have been particularly left behind. Roughly speaking, those under age 46 today, generally the Gen X and Gen Y cohorts, hadn’t accumulated any more wealth by the time they reached their 30s and 40s than their parents did over a quarter-century ago. By way of contrast, baby boomers and other older generations, or those over age 46, shared in the rising economy—they approximately doubled their net worth.

The younger cohort also faces severe disadvantages in comparison to the Boomers – severe inflation of college tuition, often leading to high level of student loan debt and the increased cost of home ownership. There’s an understandable wish for people to believe the economy is ‘getting better’, and it’s true that it’s not quite as awful as it was a few years ago. However, this is a far cry from the economy actually being good. As Brad DeLong notes about the recent unemployment figures, the employment report was fairly decent but the labor market itself is a nightmare.

“the employment-to-population ratio today is exactly where it was three-and-a-half years ago, at the recession trough…There has been no closing of the output gap and no decline in the unemployment rate from putting a greater share of the adult population to work. All of the decline in the output gap and all of the decline in the unemployment rate is from the collapse in labor force participation. {…} one-tenth of our labor market shift relative to 2007 can be attributable to demography; nine-tenths are the result of the Lesser Depression.

The parry I get from the people in Washington is: “Britain, Japan, and Europe are doing much worse!” True. So?

I’m not entirely sure how a generation that has less wealth, more debt, and a highly unfavorable labor market that threatens to last a decade are supposed to surpass the Baby Boomers in attaining a higher standard of living. As most people have intuitively known for a while, they’re not. The question that remains is – what are we going to do about that?